- Social impact

- The nature of the medium

- Face-to-face communication

- Styles of speech

- The phenomenology of using the telephone

- Social and psychological functions of the telephone

- Individual and role differences

- Teaching and learning by telephone

- The answerphone

- References

- My department is in possession of full knowledge of the details of the

invention, and the possible use of the telephone is limited. (Engineer-

in-Chief, The [British] Post Office, 1877)

- The telephone is still a medium which is answered more often than it

is questioned. (Alan Wurtzel & Colin Turner 1977, p. 259)

- While a steady stream of monographs and journal articles has

examined television, broadcasting, video, cable and satellite

communicatin, and the organization and politicization of

telecommunication, the ubiquitous, pervasive, invisible but culturally

significant connector - the telephone - has been taken for granted and

ignored. (Ann Moyal 1992, p. 51).

- Phony implies that a thing so qualified has no more substance than a

telephone talk with a supposititious friend. (New York Evening

Telegraph, 1904, cited in McLuhan 1964, p. 233)

- A woman... said she was so lonesome she had been taking a bath

three times a day in hope that the phone would ring. (cited in

McLuhan 1964, p. 233)

- The telephone is an irrestistible intruder in time or place. (Marshall

McLuhan 1964, p. 238)

- Emergency use 28.2%

- Convenience 22.1%

- Isolation Reduced 19.8%

- Time Saving 10.7%

- Business Use 6.9%

- Family Communication 4.6%

- Social Contacts 3.8%

- Other 3.8%

- Aronson, Sidney (1971): 'The Sociology of the Telephone', International Journal of Comparative Sociology 12: 153-67

- Ball, Donald W (1968): 'Towards a Sociology of Telephones and Telephoners' in M Truzzi (Ed.): Sociology and Everyday Life. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall

- Boettinger, Henry M (1976): The Telephone Book. Croton-on-Hudson, NY: Riverwood Press

- Carpenter, Edmund (1976): Oh, What a Blow that Phantom Gave me! St Albans: Paladin

- Cherry, Colin (1974): 'On communication, ancient and modern'. In David Potter & Philip Sarre (Eds.): Dimensions of Society: A Reader. London: University of London Press/Open University

- Gumpert, Gary (1987): Talking Tombstones and Other Tales of the Media Age. New York: Oxford University Press Hall, Edward (1966): The Hidden Dimension: Manís Use of Space in Public and Private. London: Bodley Head

- Ihde, Don (1979): Technics and Praxis (Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science), Vol. 24). Dordrecht: Reidel

- Livingstone, Sonia (1992): 'The Meaning of Domestic Technologies: A Personal Construct Analysis of Familial Gender Relations'. In Roger Silverstone & Eric Hirsch (Eds.): Consuming Technologies: Media and Information in Domestic Spaces. London: Routledge

- McLuhan, Marshall (1964): Understanding Media. New York: Mentor

- Moyal, Ann (1992): 'The Gendered Use of the Telephone: An Australian Case Study', Media, Culture and Society 14: 51-72

- Pool, Ithiel de Sola (Ed.) (1977): The Social Impact of the Telephone. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press Pool, Ithiel de Sola (1981): 'Extended Speech and Sounds'. In Raymond Williams (Ed.): Contact. London: Thames & Hudson

- Rutter, Derek R (1987): Communicating by Telephone (International Series in Experimental Social Psychology). Oxford: Pergamon

- Stearn, Gerald E (Ed.) (1968): McLuhan Hot & Cool. Harmondsworth: Penguin

- Wurtzel, Alan H & Colin Turner (1977): 'Latent Functions of the Telephone: What Missing the Extension Means' in Pool (Ed.), op. cit., pp. 246-61

Using the Telephone

| NB: This was written before the mobile phone boom.

|

Social impact

To advance the monocausal explanation that the telephone causes social change would reflect a naive stance of technological determinism, since technological and social factors are closely inter-dependent. However, it would be absurd to argue that changes in communication have no enabling influence on social behaviour. And the arrival of the telephone, whilst not replacing existing means of communication, contributed to changing the character of communication.

-

Early in the century... the telephone... enabled those who had moved away from old

neighbourhoods and relatives to stay in touch. It allowed friends and lovers to talk.

Perhaps, in being the counterpoint to what was happening in all the other media, it

preserved society from becoming as much of a 'mass' system as it might have

become...

The telephone... had profound... effects on the ecology of human activity. Most profound, perhaps, was the impact of the telephone on the structure of the city. From the ancient world until the turn of the last century, urban structure everywhere was a patchwork of small occupational neighbourhoods...

All that changed with trams and streetcars and the telephone. For the first time it became possible for workers to commute, for traders to travel longer distances across town, and for people to deal with each other without having to walk down the street to the other man's shop... The heart of the city became a collection of office blocks, where executives from all sorts of companies congregated far from their plants. At the same time the small single-trade neighbourhoods broke up...

Not only did business move; so did homes. The new suburbs became more attractive when one could talk with those who stayed in town...

It would be easy to interpret what we have said so far as a kind of technological determinism, and with some justification. Our lives are changed by the tools we use. But there is also interaction between the tools and men's ideas about how to use them. (Pool 1981, pp. 170-1)

The nature of the medium

Colin Cherry emphasizes the difference between the telephone and the telegraph:

-

Technically speaking, the two are closely alike, but socially they are utterly different...

The telephone... is not only personal, in the sense that private letters are, but it has far

greater significance, for the simple reason that human conversations are possible.

Conversation is an essential human relationship. When you speak to someone

on the phone, even a stranger, you hear far more than factual premeditated messages; you

respond to tones of voice, to moods; you may interject a remark; it is a person you are

involved with, not a machine. Though unseen, you continue to gesture, to smile or

frown, and move your hands; you are conversing, linked, 'involved' and 'committed'.

You can discuss, persuade, enquire, argue and perhaps reach agreement in a few

minutes, in a personal way. Rapid converse, enquiry, resolution are the powers offered

by telephones to organizations.

In private homes the telephone has added other qualities. It has enabled members of the family to travel, or even to emigrate, not only with increased security, but with less personal distress. It is the availability of the international telephone service which is of such significance to the common man today. He may not use it personally very often, but it is there. A telephone conversation means far more to, say, a mother, than any letter arriving after three days' delay or even a telegram; a call can resolve uncertainties, doubts, or anxieties and give greater assurance; even if the news told is bad, the truth can be made known. The telephone has contributed to personal mobility in a way no other medium has because the traveller does not have to stay in one place, waiting for an answer, but may continue his journey and telephone later from a callbox or hotel. (Cherry 1974, p. 116)

Marshall McLuhan suggested that when listening on the telephone, 'you have to give it all your attention' (in Stearn 1968, p. 73).

Donald Ball (1968) notes that the telephone is an insistent medium: it is difficult to resist its persistent ringing. Many people feel a sense of urgency in going to answer it. Edward Hall notes that 'Since it is impossible to tell from the ring who is on the other end of the line, or how urgent his business is, people feel compelled to answer the phone' (Hall 1966, pp. 131- 2). But he adds that English people who prefer to be alone with their thoughts or families tend to regard the phone as more of an intrusion than Americans do, and may consider callers pushy and rude when they could have written a letter instead. In a Canadian survey (Singer 1981), the greatest disadvantages of the telephone were reported (by 28.8% of users) to be interruption and personal over-accessibility: people can get in touch with you at all times, and people call who you don't want to talk to. But 58% did not make a regular practice of taking the phone off the hook.

Ball, an American sociologist, offers some unwritten rules for using the telephone which he suggests most adults have internalized:

- Although there are special exceptions, 'it is normatively defined that one is expected to, that one should answer a signaling phone's implicit invitation to interaction' (try not answering the telephone and see how you feel about this) (Ball 1968, p. 63-4);

In a Canadian survey (Singer 1981), 51.7% of their sample reported that they would answer a ringing phone in somebody else's office.

It is common for assistants to break off from serving customers in the shop to give priority to those on the telephone. The anthropologist Edmund Carpenter reported:

-

I copied down the numbers of several phones in Grand Central Station and Kennedy

Airport, and called these numbers. Almost always someone answered. When I asked why

they had answered they said, 'Because it rang'...

Some years ago in New Jersey, a mad sniper killed thriteen people then barricaded himself in a house while he shot it out with the police. An enterprising reporter found out the phone number of the house and called. The killer put down his rifle and answered the phone. 'What is it?' he asked. 'I'm very busy.' (Carpenter 1976, p. 11-12)

- one is expected to 'keep up one's conversational obligations; to participate by taking an active part in maintaining the flow of talk, even if only in the form of periodic uhs, grunts, sighs, etc.' (Ball suggests noting what happens when you do not respond) (ibid., p. 64).

The phone may also ring at any time, so that our temporal scheduling is subject to the whims of callers, whether convenient or not. In a Canadian survey (Singer 1981), 44.2% reported that they did not mind if the phone rang while they were eating; 24.8% reported that they would be annoyed or angry. 67.2% did not mind if it rang while they were watching TV. 40.6% would be startled or frightened if the phone rang in the middle of the night; 21.9% would be angry.

Ball notes that whilst what we now call 'wannabes' may seek to 'avoid obscurity' by having themselves frequently telephoned in public, some people employ avoidance strategies such as making their telephone number ex-directory, and it is a mark of high status for some to place intermediaries between callers and themselves (whether secretaries or machines). Many of us would like to decide whether we want to talk to the caller before doing so. To do this we would need to know, before answering, who the caller is, what they want, how important or urgent it is, and so on. But the phone rings in the same way whoever is calling, whatever they want.

Ball also suggests that the negation of distance by the telephone has led to the spreading of social networks and a decrease in direct social contacts.

Ball notes that 'hanging up' is a far more abrupt and irrevocable act than the nearest face-to- face equivalent of turning on one's heel. But in Singer's Canadian survey (1981), 79.2% of telephone users were prepared to hang up if the other person on the line was annoying them, whilst 6.9% felt that one ought not to hang up.

Face-to-face communication

The more frequently people make contact by telephone the more they seem to want face-to- face meetings afterwards (Rutter 1987, p. 10). When we use the telephone we have only vocal cues, but there is a rich range of cues in face-to-face communication: visual cues are important. The speaker tends to look at the listener when ending an utterance, and the other person then looks away until well under way. Gaze may be one of the signals for regulating turn-taking: looking tends to indicate a wish to communicate; averting our eyes may suggest that we want to stop talking (although it may also indicate uncertainty, stress, complexity or planning). However, nodding and hand gestures may play an even more important part than gaze in regulating turn-taking (Rutter 1987). Posture and other body language offer further cues. And in addition to visual contact, physical presence is another factor lacking when using the telephone. In face-to-face situations the whole social setting is also important: social cues matter. Rutter inteprets one experiment as suggesting that 'to make judgements about beliefs and influence, people needed verbal content, but for impressions of personality, nonverbal information was the more salient' (Rutter 1987, pp. 110-11).Styles of speech

Moscovici found that the language of back-to-back discussion resembled written language (in Rutter 1987, p. 67).The lack of social cues with the telephone (Rutter calls this 'cuelessness') tends to make it a more formal and impersonal medium for negotiation to the extent that compromise seems to be more likely in face-to-face negotiation (Rutter 1987 p. 70). Sound-only negotiation tends to be less person-centred: participants seem less concerned with the subtleties of self- presentation or with interpersonal considerations and more task-oriented than in face-to-face situations. Several experiments tend to suggest that one kind of outcome in discussion is that sound-only communication is that the strongest argument tend to prevail (Rutter 1987, Ch. 3). There is also evidence that sound-only communication can lead to a greater change in private opinions than face-to-face discussion. The most likely explanation seems to be that the less personal nature of sound-only communication may lead to speakers feeling less tense, embarrassed or threatened than in face-to-face communication and may devote more attention to the merits of the case.

Telephone conversations are normally shorter than face-to-face conversations. This may in part be because of cost and physical discomfort, but Rutter argues that 'the process of social interaction is genuinely different' (ibid., p. 83). Face-to-face discussions tend to be more protracted and wide-ranging, whereas sound-only discussions tend to keep much more to the specific issues (Rutter 1987, p. 95).

Rutter argues that that when we communicate we quickly form an impression of psychological closeness or distance based on the availability of social cues. 'According to our cuelessness model, the central difference between media is the extent to which they encourage psychological distance' (Rutter 1987, p. 99). Usually, Rutter suggests, 'when social cues are denied us... we feel distant psychologically... Cuelessness leads to psychological distance, psychological distance leads to task-oriented and depersonalised content, and task-oriented, depersonalised content leads in turn to a deliberate, unspontaneous style and particular types of outcome [less likelihood of compromise]' (Rutter 1987, p. 74). Rutter adds that 'cuelessness remains firmly an informational concept, but the link between cues and behaviour is phenomenological' (Rutter 1987, p. 137).

However, Rutter also notes that 'in hotline counselling... the whole point of the system is that the telephone allows and encourages the very psychological proximity and intimate content which is normally possible only face-to-face - but this time it is the anonymity which produces psychological proximity, and the role of cuelessness is to make that anonymity possible' (Rutter 1987, p. 97). He adds that 'Cuelessness is only one of the determinants of psychological distance and proximity' (Rutter 1987, p. 97). Others include task, role, and the relationship between the participants: 'though typically they will work together in the same direction, they will almost certainly have variable weightings, and they may sometimes even conflict' (ibid.). 'Each is likely to have its own independent effects upon psychological distance, but those effects will probably change with time, and the variables will in any case interact' (ibid., p. 137).

John Short, Ederyn Williams and Bruce Christie of the Communications Study Group at University College, London emphasized the importance of what they called the Social Presence of a medium:

-

We regard Social Presence as being a quality of the communications medium.

Although we would expect it to affect the way individuals perceive their discussions,

and their relationships to the persons with whom they are communicating, it is

important to emphasize that we are defining Social Presence as a quality of the

medium itself. We hypothesize that communications media vary in their degree of

Social Presence, and that these variations are important in determining the way

individuals interact. We also hypothesize that the users of any given communications

medium are in some sense aware of the degree of Social Presence of the medium and

tend to avoid using the medium for certain types of interactions; specifically,

interactions requiring a higher degree of Social Presence than they perceive the

medium to have. Thus we believe that Social Presence is an important key to

understanding person-to-person telecommunications. It varies between different

media, it affects the nature of the interaction and it interacts with the purpose of the

interaction to influence the medium chosen by the individual who wishes to

communicate... We conceive of the Social Presence of a medium as a perceptual or

attitudinal dimension of the user, a 'mental set' towards the medium. Thus, when we

said earlier that Social Presence is a quality of the medium we were not being strictly

accurate. We wished then to distinguish between the medium itself and the

communications for which the medium is used. Now we need to make a finer

distinction. We conceive of Social Presence not as an objective quality of medium,

though it must surely be dependent upon the medium's objective qualities, but as a

subjective quality of the medium... We believe that it is important to know how the

user perceives the medium, what his feelings are and what his 'mental set' is. (cited in

Rutter 1987, pp. 132-3)

They found that users ranked various media in decreasing order of Social Presence thus: face-to-face, video links, the telephone, monaural audio and the business letter. They argued that various tasks might require more or less Social Presence and that with simple tasks involving 'information transmission' or problem-solving, which require little Social Presence, the medium used matters less. They also added that 'apparent distance' would be influenced by the number and types of media available to participants:

-

For example, if a person uses his telephone to speak to someone in an adjacent office

when it would be just as convenient to go and see him, an impression of 'distance' and

non-immediacy is likely to be created, especially if the person making the call is the

other's superior. However, the non-immediacy associated with the use of the telephone

in this instance is less likely to be replicated when the two parties are separated by

considerable physical distances. In these cases, where face-to-face communication is

not practicable, the use of the telephone does not carry the same connotation.

Although immediacy varies in these two kinds of situation, the Social Presence

afforded by the telephone will be the same (unless, of course, the quality of sound is

affected by the distances involved; if so, Social Presence will be greater not less,

when the two parties are in adjacent offices). (cited in Rutter 1987, pp. 135-6)

56.2% of users felt that most people would not or could not discuss their personal lives over the phone. This included personal or emotional problems, sex life, health, marital or family problems, religion, funerals or sickness. Reasons for avaoidance of topics varied: others in the room might be listening; others might be listening in on the line; the matter might be to complex for the phone. Benjamin Singer suggests that some matters are 'almost taboo' for discussion on the phone (ibid., p. 74). However, a surprisingly large proportion - 15.7% - felt that they could discuss anything over the telephone.

The phenomenology of using the telephone

Don Ihde, a philosopher, argues that particular media select and amplify some dimensions of experience and reduce others:

-

I pick up the telephone to call a friend. Once he picks up the phone at his end and

speaks I find once again that I experience him through the telephone. I speak and

listen to him and if the connection is good the phone does not intrude primarily into

our conversation... There clearly is... an extension of my experience - I speak to my

friend from my home, overcoming geographical distance in a temporal instant.

Moreover, if the technology is good the distance makes little difference. In fact, I

could have the same experience of my friend whether he were in California of in

Holland or next door. Note, of course, that there is a subtle and deep transformation

implied here in relation to an experienced spatiality. There is an almost constant 'here

and now' quality of the other through the telephone, a deconstruction of certain kinds

of distance. Nevertheless, the telephone 'extends' my hearing to the distant other.

However, at the same time, this extension is also a reduction in several ways. First, it is clearly a reduction of the full range of my globally sensory experience of the other. Thus, speaking through the telephone is minus the rich visual presence of the other in a face to face conversation. Imagine a variation within this reduced experience - I am speaking, rapidly, and engrossed in what I am saying, and I hear a regularly repeated 'yes', 'yes', 'oh', etc. But I do not see the yawns which accompany these words or, even worse, the facial gestures of chagrin and boredom. These remain absent and hidden from me. The other is only partially present, a quasi-presence or transformed presence. I am extended to the other, but the other is a reduced presence. This is, of course, even true of the auditory presence as well. I can recognise that it is indeed my friend who is speaking, but his speaking is 'tinny' and 'phony' when compared to the fullness of his voice while speaking face to face...

The experience is a transformed experience which has a difference between it and all 'face to face' or 'in the flesh' experiences. This transformation contains the possibilities... of both a certain extension and amplification of experience and of a reduction and transformation of experience...

It is easy to see that this instrument falls in certain ways into the 'information gathering' function of technology... it is to the other that I address myself. The phone becomes the means and is semi-transparent in my use of it...

The phone may be called a 'mono-sensory' device, it reduces the other to a voice... The ratio of amplification to reduction is more dramatic in some [cases] than others. The phone is sufficient in some cases, while relatively inadequate in others, and what is of importance is to discern towards what kinds of situations the sufficiency increases... In some respects this is only to note that the telephone is, after all, more appropriate for some functions than others, and in that regard it simply embodies some social purpose. But in other respects I am suggesting that insofar as technologies are non-neutral they have a reflexive amplificatory-reductive effect as well. (Ihde 1979, pp. 9-10, 23-4, 26)

Social and psychological functions of the telephone

In a Canadian survey (Singer 1981), the following major advantages of the telephone were reported:

Singer notes that these categories can be grouped thus: pragmatics and coping with the world, 69%; sociational or psychological dimensions (isolation reduction, social contacts), 22%.

According to Sidney Aronson, an American sociologist (1971), in an urban setting the home phone functions psychologically to reduce loneliness and anxiety, to increase feelings of security and to maintain cohesion within family and friendship groups. The telephone is used to compensate for (as well as facilitate) the geographical scattering of family and friends. Aronson (1971) suggests that a key social function of the telephone is in maintaining its users' 'intimate social networks' or 'psychological neighbourhoods'.

Alan Wurtzel and Colin Turner surveyed the reactions of Manhattan telephone users after they had been subjected to a 23-day loss of service (caused by a fire) in 1975. 90% of the 190 people questioned felt that the telephone was a necessity. Wurtzel and Turner also reported that 'people judge the phone more necessary as they grow older' (ibid., p. 256).

Relatively few people increased their use of other modes of communication during the phone blackout, supporting the idea that 'the home phone has a distinctive role in communication behaviour' (Wurtzel & Turner 1977, p. 251). As Aronson had argued, this social function did involve maintaining one's 'psychological neighbourhood'. People most missed calls from and to friends and family. Again as Aronson had suggested, the telephone also had a psychological function in reducing loneliness and anxiety and in increasing feelings of security. When it was out of order over two-thirds of the sample felt 'isolated' or 'uneasy'.

To most people on Manhattan's Lower East Side, there was no satisfactory alternative to the telephone... From most in the sample, neither the exchange of letters not the one-way flow of mass communications could be made to substitute for the immediate interaction provided by the telephone... The telephone seems to reduce the amount of unmediated socialization among friends and family who still live near the caller... The telephone, in other words, both gives and takes away; though it may reduce loneliness and uneasiness, its likely contribution to the malaise of urban depersonalization should not be underestimated. Such ironies are now an old story: a technological device eventually is used in solving a problem it has helped create' (Wurtzel & Turner 1977, p. 255-6).

They add that 'since conducting the survey, we have encountered much anecdotal data on the increase of interactive street life and community awareness during the blackout period. These sources also noted that once the telephone system was restored, the interactions attenuated and the community awareness abated' (ibid., p. 260).

Despite the widespread acknowledgement of the social and psychological importance of the telephone, 47% of the sample agreed that 'life felt less hectic' without the telephone, and 42% said that they 'enjoyed the feeling of knowing that no one could intrude on me by phone':

-

The minority who enjoyed the blackout's lack of intrusions served to qualify (though

not deny) this fundamental function of the telephone ['the maintenance of symbolic

proximity' in the 'psychological neighbourhood']. Together with the response of those

who found life less hectic without the phone, the sense of relief from intrusion reveals

an ambivalence toward the medium that relates to the tradeoff of distance for time and

privacy for accessibilty. Though the telephone fosters mobility by promoting instant

contact, it also annexes an individual to all those who have his phone number; though

it dispels isolation by providing open channels, it also puts a person at the mercy of

others' communicative needs. The telephone might bolster the urban dweller's feelings

of control, but it exacts a price in interruptions and the unchosen investment of time.

Such compromises seemed less tenable to those who enjoyed the blackout's freedom

from intrusions' (ibid., p. 257).

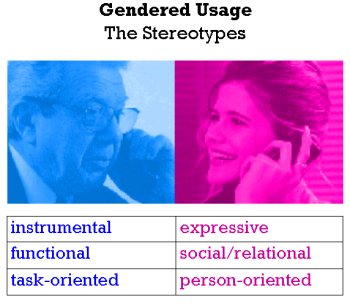

Individual and role differences

RELATIONSHIPS. Friends look more than strangers, probably because they have less need for information about each other's beliefs and attitudes (Rutter 1987).

GENDER. Women engage in more eye-contact than men, perhaps from a greater need for

affiliation or because they are more dependent on social cues and feedback. But of available

domestic technologies, women often tend to value most those which facilitate social

contact, and may rate most highly the telephone and the car (whereas men often tend to

value technologies which offer alternatives to social contact). The telephone offers many

women the pleasure of emotional involvement and is typically regarded as a vital connection

to friends and family . Men, on the other hand, tend to treat the telephone more

instrumentally or associate it with an invasion of their home space by work. Sonia

Livingstone suggests that at home 'men regard the telephone with irritation, suspicion and

boredom, they see little point in chatting on the phone, avoid initiating a call, and often

prefer not to answer' (in Silverstone & Hersh 1992, p. 122). Wurtzel and Turner's (1977)

Manhattan survey found no gender-based differences on the questions they asked about

telephone use. But Ann Moyal's Australian survey found 'distinctive feminine patterns of

telephone use' (Moyal 1992, p. 54). 184 of the 200 women surveyed said that the prime

importance of the telephone in their daily lives was 'sustaining family relationships' (ibid., p.

55). Close friendship calls also had a high priority with women. 'the survey's reiterated

finding... was that women talk more freely and intimately on the telephone with close

friends than they do face-to-face, that the telephone highlights warmth and sympathy in the

voice, that (as one respondent put it) 'you can convey "greater depth in conversation on the

telephone"' (ibid., p. 58). Specific reference was made by one woman to the 'psychological

neighbourhood' created by the telephone. 'Many attested that telephone had replaced letters,

the telephone was a major transport replacement and for some their only means of

maintaining important feminine networking' (ibid., p. 64).

PERSONALITY. Extraverts tend to be more verbally productive in speech than introverts;

their speech is characterised by fewer silent pauses than that of introverts (Rutter 1987, p.

49). 'Impulsivity' is a cognitive trait closely associated with this feature. However,

personality should not be considered in isolation from situational factors.

There was no evidence of differences between the media in terms of task-orientation (which

was very high) or personal content (of which there was little). However, there was greater

structuring over the phone and greater spontaneity face-to-face. On the telephone students

spent more time discussing their own ideas than in face-to-face tutorials, but in shorter

utterances (their total contributions were no greater). It is easier to ensure a more equitable

distribution of time to each student over the telephone, whereas verbose individuals can

easily dominate face-to-face tutorials. Questions to particular students were more numerous

over the phone than in face-to-face tutorials. Tutors said much more over the phone than

face-to-face. Students interrupted almost twice as frequently face-to-face as over the phone.

The telephone style was less spontaneous and more formal (and was acknowledged as such

by participants). Face-to-face students also asked more questions of their own whilst

devoting less of their utterances to answering questions from the tutor (Rutter 1987, pp.

151-8). A later study showed that the use of the telephone was also associated with more

rigid tutor-student patterns whereas face-to-face tutorials involved as many exchanges

between students as between tutor and student.

The caller's relationship with the answering unit is often strange, sometimes bizarre.

Just after the telephone ring is interrupted by the answering voice there is a moment of

indecision when the cerebellum has not yet distinguished a recording from the real

voice. One breaks off in mid-word with the embarrassing realization that no one is

listening. The caller feels a twinge of hostility at being cheated by both the telephone

company and by the person being called, the former because it has completed a call to

a tape recorder for which there is a charge and the latter because it has reduced a

relationship to that of a deposited message...

Once the tape-recorded instructions begin - "please leave a message after the beep" -

anxiety accelerates. The intimidation grows as the time of the magic beep approaches;

there is a Pavlovian aspect to the whole affair. Because the device has reduced the

caller to a thirty-second response, a surge of adrenalin prepares the victim for a race

against the clock. The diabolical machine's egalitarian premise is that anyone can be

reduced to thirty seconds... The fact that an innocuous message is being recorded

exaggerates its importance. Some people have great difficulty with the knowledge that

they are being recorded and quickly hang up without leaving a message (a possibly

faltering message could become a public document). The hang-up percentage must

be at least 50%. Whether it is intentional or not, the interaction between a caller and

the answering machine is manipulative. Instead of a human voice, the caller is greeted

by the metallic filtered voice of the respondent politely and cleverly explaining that he

or she is not there and that at the sound of the beep one is to leave a coherent message.

The focus is shifted from interaction to response, and everyone rehearses for the

performance. (Gumpert 1987, pp. 133-6)

Daniel Chandler

This page has been accessed

Teaching and learning by telephone

Tutors at the Open University saw no particular advantage in tutorials being conducted

either face-to-face or over the phone. However, students in the East Midlands reported that

telephone tutorials were academically more satisfactory than face-to-face tutorials for

specific guidance on topic areas and also for remedial assistance. For summarizing the

printed course materials they felt that these modes were much the same. But they thought

that face-to-face tutorials were better for moral support from the tutor. They felt that the

main advantage of telephone tutorials was that they were more efficient in the use of time.

However, almost half preferred face-to-face tutorials, and almost all respondents reported

that telephone tutorials made them feel anxious. The answerphone

Gary Gumpert, Professorof Communication Arts and Sciences at Queens College, City

University, New York insists that:

Communication with a machine is in contradistinction to communication with another

human being... The addition of the answering machine to the accoutrements of

communication points to the importance of connection. 'Could the telephone have

rung while I was out?' Everyone has desperately grappled with the door key

attempting to get to the ringing phone before it is too late - and failed... [Besides

business reasons] the motivation behind buying an answering machine includes the

need to screen calls, a desire to establish status by interposing the machine betewen

oneself and the caller (only busy people require an answering unit), and the neurosis

of having to know if someone might have tried to call.

References

UWA 1994 times since 18th September 1995.