fig. 1

Jamming is CB slang for the illegal practice of interrupting radio broadcasts. It describes various kinds of media sabotage such as computer hacking, pirate radio stations camcorder counter surveillance groups and subvertising (Dery 1993, www).

It the early days the 'cultural jams' of the subvertiser consisted of scrawling an oppositional message in graffiti to the preferred reading of the advert (to use Stuart Hall's terms). For example in the 1980s, feminists graffiti artists sprayed "feed me" over the anorexic looking models that graced fashion ads. Jill Posner (1982) argues,

A billboard without graffiti is something quite outrageous, because billboards are not only grossly ugly but they also mislead and misinform the consumer with at the same time teasing use with the products they are promoting.

Billboards are claimed by subvertisers to be socially destabilising, because they exploit the weakness of certain demographics to oppose their messages. Poor neighbourhoods have a disproportionately large number of advertisements for tobacco, fast food, or alcohol products (Klein, 2000).

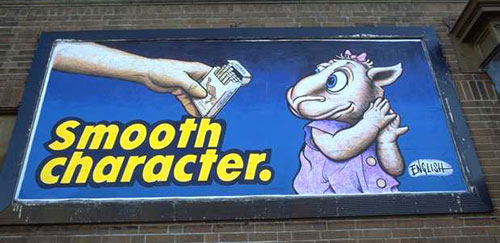

fig. 2

The strategy of Camel cigarettes for example seems to be to entice very young consumers into smoking. The cartoon character of Joe Camel has an obvious appeal to children. For instance a 1991 study found that children in the US were as familiar with Joe Camel as they were with Mickey Mouse (Goldman and Papson 1996, 3). In Fig 2, this strategy is laid bare for all to see. Reversioning the character Joe Camel as a toddler calls attention to the real audience of consumers that the subvertisers claim Camel is targeting with its advertising.

Subvertising rejects the idea that the messages of advertisers should be allowed to be displayed in letters six feet high on billboards, while citizens are denied a right to reply. In the conversation between citizen and advertiser, they argue the rights of the former are skewed in favour of the latter because an advertisers can afford to buy their way into dominating public spaces. Where billboards proliferate, a commercial cacophony of voices has risen to such a pitch that no one can hear anyone else. Consequently free speech is meaningless in those spaces (Klein).

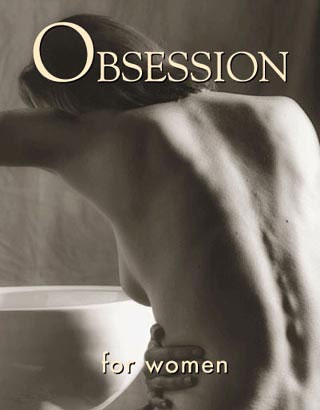

In recent years the subvertising aspect of cultural jamming has extended to print and even television advertising, with the rise of groups like Adbusters (fig. 3).

fig. 3

The growth in computers and easily affordable digital image manipulation programs like Photoshop has meant that the techniques of the subvertiser have grown more sophisticated. Allowing her or him more scope for turning the messages of the advertising agencies against themselves

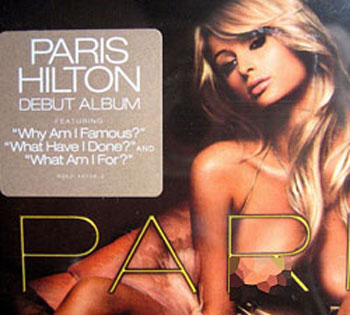

fig. 4

For example the guerrilla artist Banksy recently reworked several thousand copies of Paris Hilton's debut album (fig 2) which were then sequestered back into record stores ostensibly to masquerade as the genuine product. Banksy only admitted to the tampering with the CDs once the 'hack' had been discovered. Presumably this means a number of unsuspecting record buyers were duped by Banksy, or pleasantly surprised by Ms. Hilton's confessional candidness. Either way it meets Posner’s criteria of a successful subvert, because it sticks in the mind and makes a sharp point within a humorous framework (Posner 1982)

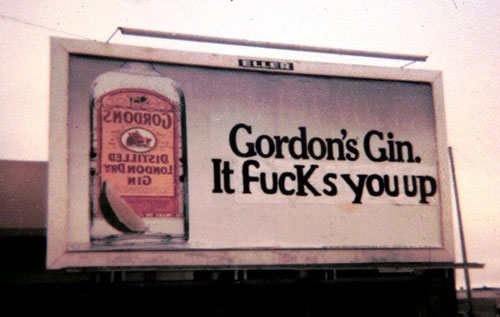

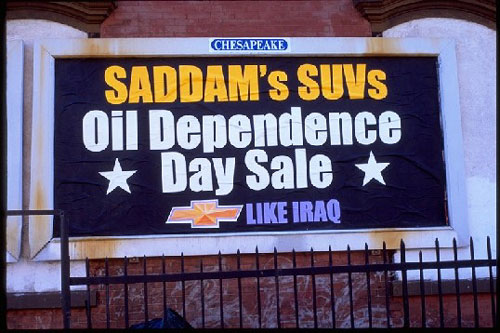

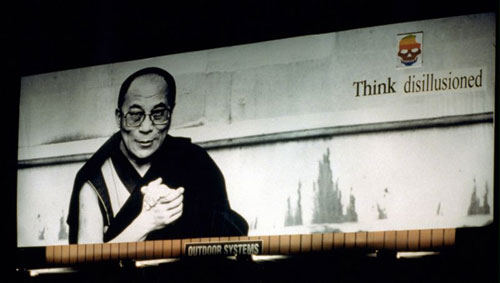

According to Naomi Klein, the most sophisticated culture jams are an x-ray of the subconscious of an advertising campaign, uncovering not an opposite meaning but a deeper truth behind the layers of euphemisms, as figures 5, 6, and 7 illustrate.

fig. 5

fig. 6

fig. 7

The process is doubly subversive firstly because it forces the company to foot the bill for the defacing of its property - since the billboard space is already paid for. And secondly because the success of advertising is premised on the notion that generating positive visual associations adds value to the brand (Klein).

The added value is vastly important because as Goldman and Papson explain, in today's consumer goods markets, product standardization makes it imperative that products attach themselves to signs that carry an additional element of added value to differentiate them. A sign value establishes the relative value of a brand where the functional difference between products is minimal. For example the similarities between a trainer from Woolworth and a trainer from Nike are much greater than the differences, although Woolworth trainers do not have the slogan "Just do it" nor do they have stars like Michael Jordan and Wayne Rooney endorsing their product. The competition to build images that stand out in media markets is based on a process of routinely unhinging signifiers from signifieds so that new signifier-signified relationships can be fashioned. But this process of establishing new signifier/signified relationships is a delicate balance. The C.E.O. of Nike Phil Knight articulated the challenge in the following way:

There is a flip side to the emotions we generate… emotions imply their opposite and at the level we operate, the reaction is much more than a passing thought (quoted in Klein 200).

This semiotic balancing act explains partly the success of subvertising. The essential arbitrariness of the relationship between signifier and signifies as described by Saussure in the Cours de Linguistique gènèrale means that one a negative association is introduced it can soon become a connotation of a companies branding. For example McDonalds as a brand are as much associated with McSpotlight and Morgan Spurlock's film Super Size Me (2004) as they are with the Big Mac and Ronald McDonald. A successful subvert means that you will never look at a campaign in quite the same way again. Also after the public relations disaster that was the McSpotlight trial, where McDonald's tried to sue two London Greenpeace activists for liable, companies are also reluctant to get involved with litigation. For instance Pepsi only comment on a Negativeland song The Greatest Taste Around, which associated their brand with increasingly surreal negative imagery, was that it was a pretty good listen (quoted in Klein).