- The main elements

- Methodology

- Data gathering and analysis

- Discussion and conclusions

- Presentational issues

- Readability

- Illustrations

- Reference format

- Structure and word counts

- Other presentational Issues

- Dissertation Template (Word)

- Further reading

- Dissertation Feedback Form

Writing Your Dissertation

Some Guidelines for University Students

Daniel Chandler

Page Contents

Proposing a Topic

Your choice of topic for research is likely to be influenced by such factors as:

- relevance: its perceived relevance to the academic department(s) in which you are studying;

- supervision: the availability of tutors/supervisors within the department(s) who are interested in the topic and their willingness to supervise such a dissertation;

- interest: your existing knowledge of that topic and the strength of your desire to learn more about it;

- competence: your likely ability to employ the proposed methods of data gathering and data analysis;

- scale: the feasibility of completing the study within the time and resources available.

Most university departments have profiles of their academic staff which list their main areas of research interests, so check these. You may be required to demonstrate that your proposed topic is viable in the light of such factors. In particular, try to choose a topic in which you are genuinely interested.

Undergraduate students of media and communications are often tempted to propose 'effects research'. Quite apart from being wholly impractical with a limited time-scale and no budget, this approach has been subjected to extensive academic criticism. If you are tempted to research 'how the media influence people', read David Gauntlett's 'Ten Things Wrong with "The Effects Model"' (Gauntlett 1998).

For a research degree as such (MPhil, PhD) you are usually expected to provide a formal research proposal. Indeed, your acceptance for a research degree may depend on the submission and approval of such a formal proposal as part of your application. Such a proposal needs to include the title (even if that might change over time), a clear explanation of the academic (rather than personal) importance of the topic with reference to some existing published research in the field, an outline of a proposed methodology for data-gathering and also for analysis, and a provisional schedule for key stages in the work tied to dates in the calendar.

Framing a research focus

For the purposes of your initial proposal, you need to frame your topic as clearly as you can at this stage (even though it may alter over time). As an example, if your topic is representation, consider:

- What will be your focus in terms of identity (e.g. gender, sexuality, race or class)?

- What will be your focus in terms of genre (e.g. advertisements, feature films, trailers)?

- What will be your focus in terms of medium (e.g. newspapers, magazines, film, TV, social media)?

- What will be your focus in terms of the representational process (e.g. production factors, audience factors, formal features, regulation)?

- What will be your primary methodology? (e.g. if it’s with me, it is semiotic analysis).

- What will be your historical focus (e.g. a specific day, month, season, year or decade)?

- On which country (or countries, in the case of comparisons) will you focus (e.g. UK, Poland, Bulgaria)?

An example would be: 'A semiotic analysis of visual cues to social status in British magazine advertisements in the Summer of 2012'. This is the provisional title of your dissertation and your final title will be in much the same form (though the wording may well change). Insofar as the title is part of your initial proposal it needs to be the kind of question that your tutors regard as worthy of investigation, so you need to put a lot of effort into getting this right. It is usually wise to restrict it to a single sentence and to make your topic self-evident from this. However, if the sentence is rather long a subtitle is acceptable (after a colon): the short form can then be conveniently printed on the spine of a hard-bound dissertation. The specific research question(s) that you will address will depend on your rationale and theoretical framework.

Rationale and theoretical framework

You must include a rationale: an explanation of why you are studying the topic and of why it is important. You will need to show evidence that specialists in the field do find it important. It is not good enough to say that you find it personally interesting (you shouldn't be studying it otherwise!). Think of your reader(s). In justifying your study it can be useful to imagine a cynical critic who cannot imagine why anyone would waste their time on such a study! If you can address their concerns you will be doing well. You could ask one of your friends to play 'Devil's Advocate' for you to check how persuasive you are being. On the other hand, bear your specialist readers in mind and don't try to explain terms that should already be familiar to them: just demonstrate that you understand such terms by the way in which you apply them throughout your study.

A theoretical framework often features as an early section in a dissertation. Firstly, you must make explicit the particular academic discourse within which your study is framed. It should be clear (to the reader) from the outset that your approach is (for instance) historical, psychological, sociological, philosophical, semiotic or linguistic (be wary about stepping outside the specialisms into which you have been inducted within your department, though your topic area may straddle traditional disciplinary boundaries). Within any given discipline you also need to locate your study within a relevant sub-discipline or branch of the subject (e.g. social psychology or visual semiotics) and then within a particular tradition or 'school of thought' (e.g. social constructionism or queer theory). In a theoretical framework you would include an outline of existing theories which are closely related to your research topic. You should make clear how your research relates to such theories. Who are regarded as the key theorists in the field on the central issues involved? You should find some names coming up repeatedly (these will later appear in your literature review). Justify your choices. If you can't identify key theorists this suggests that your topic lacks theoretical interest. What are the key debates and what arguments and evidence have the key theorists put forward? What questions remain unresolved? What key concepts that feature in your study are disputed and which of the competing definitions are you adopting or challenging (see, for instance, Chandler & Munday 2011 for different definitions of key concepts within Media and Communication Studies). How are 'research questions' in the field framed? How does your own research relate to such framings? You should make your own theoretical assumptions and allegiances as explicit as possible. Later, your discussion of methodology should be linked to this theoretical framework.

Your research should be guided by a central research question (or a series of closely-connected questions). This needs to be made explicit early on (although you may refine your question(s) as your understanding deepens. Your research questions will help you to stay on target and to avoid being distracted by interesting (but irrelevant) digressions. Your markers/examiners will need to consider whether, by the end of your dissertation, you have adequately answered the question you set yourself. Consequently, it needs to be viable: possible to address in the timescale and budget available and using the proposed methodology.

Reviewing the literature

Academic dissertations at all levels in the social sciences typically include some kind of 'literature review'. It is probably more useful for students to think of this, as examiners usually do, as a 'critical review of the literature', for reasons which will be made clear shortly. The literature review is normally an early section in the dissertation.

The broader survey

Students are normally expected to begin working on a general survey of the related research literature at the earliest possible stage of their research. This in itself is not what is normally meant in formal references to the 'review of the literature', but is rather a preparatory stage. This survey stage ranges far wider in scope and quantity than the final review, typically including more general works. Your survey (which exists in writing only in your notes) should help you in several ways, such as:

- to decide on the issues you will address;

- to become aware of appropriate research methodologies;

- to see how research on your specific topic fits into a broader framework;

- to help you not to 'reinvent the wheel';

- to help you to avoid any well-known theoretical and methodological pitfalls;

- to prepare you for approaching the critical review.

The 'critical' review

Clearly, if you are new to research in the field you are not in a position to 'criticise' the work of experienced researchers on the basis of your own knowledge of the topic or of research methodology. Where you are reporting on well-known research studies closely related to your topic, however, some critical comments may well be available from other established researchers (often in textbooks on the topic). These criticisms of methodology, conclusions and so on can and should be reported in your review (together with any published reactions to these criticisms!).

However, the use of the term critical is not usually meant to suggest that you should focus on criticising the work of established researchers. It is primarily meant to indicate that:

- the review should not be merely a descriptive list of a number of research

projects related to the topic;

- you are capable of thinking critically and with insight about the issues raised by

previous research.

What is a literature review for?

The review can serve many functions, some of which are as follows:

- to indicate what researchers in the field already know about the topic;

- to indicate what those in the field do not yet know about the topic - the 'gaps';

- to indicate major questions in the topic area;

- to provide background information for the non-specialist reader seeking to gain an

overview of the field;

- to ensure that new research (including yours) avoids the errors of some earlier research;

- to demonstrate your grasp of the topic.

Your literature review is a preparation for your own research. It is part of the research process but it is not in itself 'research'. Don’t write ‘according to my research...’ if you mean ‘according to what I have read...’. Simply reading what others have written about your research topic is not research. That's why we refer to this activity as a 'literature review' rather than as 'literature research'. Library work is scholarship rather than research: scholarship involves seeking knowledge; research involves creating it. When Wilson Kizner wrote, 'To steal ideas from one person is plagiarism, to steal ideas from many is research', he was, of course, being satirical. Of course, if your subsequent research involves some form of textual analysis, then that analysis would indeed be research.

What should I include in a literature review?

The formal review is not a record of 'what I have read' and your 'literature review' is not like a series of book reviews. A literature review summarises what reputable researchers have already discovered about a particular research question. The main items discussed are not usually entire books, but more often papers in academic journals or chapters in specialist academic books. They should include only published research studies: not introductions to a subject, or purely theoretical works, for instance. You can (and should) refer to broad theoretical works in your introduction, and you can refer to works about methodologies in your Methodology section (rather than in your Literature Review). You should refer back to all such works when related issues are discussed in your own study (especially in your discussion of your own findings).

Your supervisor may be able to direct you to a published literature review as an exemplar of the general format expected. If a literature review of a closely-related topic has already been published, you should 'set the scene' by referring to this first before discussing research published since that review appeared.

In the formal review of the literature you should refer only to research projects which are closely related to your own topic. If your problem is how to choose what to leave out, one way might be to focus on the most recent papers. You should normally aim to include key studies which are widely cited by others in the field, however old they may be. Where there are several similar studies with similar findings, you should review a representative study which was well designed.

Some tutors encourage their students to refer to a range of relevant projects representing various research methodologies; others may prefer you to concentrate on those employing the methodology which you intend to use (e.g. experiments or field studies). Where you have been advised to review studies representing different methodologies, do not over-represent any single methodology unless it represents that which you intend to use.

If you find that very little seems to exist which is closely related to your topic you should discuss this with your supervisor. In such a case the most obvious options would be either to widen the net to include less closely-related studies or to reduce the length of the review. However, you should make quite sure that your search for relevant papers and books has been adequate.

Wherever possible, your discussion of each published research study should include details such as:

- the names of the primary researchers

- the formal title of the study

- the funding body or bodies involved

- the department(s) and institution(s) where these were based at the time

- the academic disciplines of the researchers (e.g. psychology, sociology)

- the year(s) when it was conducted (as well as where and when it was published, which should appear in your References list, of course)

- the country or countries in which it was conducted (together with any more specific information on region, cities etc.)

- the sample size and composition (and how it was selected)

- why the study was undertaken

- the key research questions which it sought to address

- the methodology or methodologies employed (in as much detail as possible in the available space)

- the main findings, especially those most closely related to your own study

- the limitations of the study (as noted by those involved as well as by any subsequent commentators) - particularly any methodological limitations (especially where you will be employing a similar methodology)

- any issues which it failed to resolve and any further research questions that it raised (especially where you will be addressing any of these)

- how it relates to similar published research studies (especially others reviewed here by you), including whether or not it replicates any particular findings

Where should I look?

Always start by asking your supervisor for some suggested initial reading. Your institution's libraries should (still) be your next port of call. Undergraduates may not until now have made regular use of specialist academic journals - the serious journals are an essential resource for your dissertation, regardless of whether they are in print or online. Your university library should be able to advise you how to locate relevant articles in such journals. For other online documents, begin by checking for specialist on-line academic 'portals' (again, your supervisor may know some). For research purposes, you should not rely on online sources which lack details of author and date, including Wikipedia.

If you still cannot find relevant research publications, your tutor may suggest that you should review more loosely-related studies which nevertheless employed the research methodology which you are intending to use.

At Aberystwyth University we are fortunate to have a National Library on our doorstep: any of our students undertaking a dissertation should make as much use as possible of this invaluable resource. Books and journals not in our own stock or in that of the National Library can be obtained (for a fee) using the Inter-Library Loans service within the university library.

As for non-book materials the topic is too vast to cover here. However, some videoclips are available online. Commercials in particular are quite widely available on YouTube (although not always the ones you wanted!). For guidance on capturing stills from film or television, click here.

How long should a literature review be?

This varies and the attitudes of your supervisor and examiners must be taken into account: some supervisors allow undergraduate students to devote the bulk of a mini-dissertation to a literature review; others insist on some element of original research. As to how many research studies you should review, this varies too. You should not review so many that you can devote little space to each.

Methodology

A section on methodology is a key element in a social science dissertation. Methodology refers to the choice and use of particular strategies and tools for data gathering and analysis. Your choice of methodologies should be related to the theoretical framework outlined earlier. Particular methodologies are usually well-established within the particular tradition and 'school of thought' with which you have allied your study and reflected in the academic work that you have reviewed. Some methodologies embrace both data gathering and analysis, such as content analysis, ethnography and semiotic analysis. Others apply either to gathering or analysing data (though the distinction is often not clearcut):

- data-gathering methodologies include interviews, questionnaires and observation;

- data analysis methodologies include content analysis, discourse analysis, semiotic analysis and statistical analysis.

There are many varieties of each methodology and the specific methodological tools you are adopting must be made explicit. Interviews, for instance, are often categorized as 'structured', 'semi-structured' or 'open-ended'. You should mention which other related studies (cited in your literature review) have employed the same methodology. Note that 'textual analysis' as such is not a methodology - it is a focus; if you are focusing on texts (in any medium) you need to specify what form of textual analysis you are going to use: for instance, semiotic analysis, content analysis or discourse analysis.

A key practical consideration when deciding on your methodology is your own competence and confidence in using the selected methods. For instance, do not attempt a psychoanalytical approach to textual analysis unless you and your supervisor are confident that you can handle this (and that this is appropriate and acceptable). Ideally you should use a method you have successfully employed before. If you need further training or advice in using your chosen method, seek out local academic advice from someone who regularly uses that method. Always consult methodological handbooks in your topic area for guidance on issues and pitfalls. It's a good practice to consult several of these when you prepare your methodological section. In addition, you should read several published academic papers in related topic areas which employ a similar methodology to the one you are planning to use. You are not expected to invent the tools that you use, although the way that you apply them may be novel and you will probably be applying them to different materials. Check out some student dissertations which you know were regarded as acceptable within your course: their discussions of methodology might give you some pointers for yours.

The section on methodology should include a rationale for the choice of methodology for data gathering and for data analysis. In the rationale you should consider what alternative methodological tools might have been employed (particularly those which related studies have employed), together with their advantages and limitations for the present purpose. For instance... Why did you choose to undertake interviews? Why open-ended interviews? Why did you opt for audio-recording (for instance)? Refer to a relevant study which approached interviews in a similar way. Cite a reputable study which selected participants on a similar basis. On what basis did you choose your participants (that they were friends of yours with time on their hands is not an adequate justification!). If there are any obvious segments of the population which are not represented within your sample why is this? Where class, age, gender and/or ethnicity is likely to be involved in the phenomenon you are studying then make sure that your sample is demographically appropriate. What limitations of your sample should your readers be alerted to?

If data can be counted it is quantitative; otherwise it is qualitative. Often one or the other kind of data predominates in a study, in which case this may reflect the tradition or school of thought within which the study is framed. However, qualitative and quantitative approaches are not seen as incompatible within all academic research traditions: many studies (such as research into advertising) do successfully combine both approaches (e,g. content analysis and semiotic analysis). If you are excluding either quantitative or qualitative data, you need to explain why you are doing so. How does your decision relate to the approaches adopted in the literature you have reviewed?

Relevant ethical issues need to be discussed. You are advised to seek special guidance on this from your supervisor since the issues involved are highly dependent on the specific study. Note that investigations involving children and vulnerable persons require special protocols and this may not be practicable for undergraduate dissertations. For adults, here is a sample Consent Form for Interviews, Photography and Recording, but once again, your own institution is likely to have its own forms.

Data gathering and analysis

Data should be presented as clearly as possible for the reader. Above all, when reporting empirical data start off by telling readers basic details such as:

- how, when and where the study was conducted;

- how the sample was selected;

- the reasons for this form of selection (even if was simply a 'convenience sample');

- the total number of respondents (if you used a survey) or informants (if you used interviews);

- demographics relevant to the study (e.g. the total number of males and females or of those in particular age-groups);

- the reasons for any demographic imbalances.

Where it makes patterns clearer to readers, use graphical displays such as bar-charts or pie-charts. Wherever possible you should present your readers with sufficient data in an appendix for them to test your approach and to draw their own conclusions. There is no data without a theory, so you need to underline the theoretical basis for your selection of relevant data. Data does not ‘speak for itself’: it requires interpretation. Methods of interpretation vary widely but note that you must adopt some recognised method and definitely not appear to 'make it up as you go along'! Try to follow the practices employed in some relevant and reputable published study.

Online forms can be useful to gather data, although remember to note that this affects the character of the sample - skewing it in favour of those with internet access who go in for online surveys.

|

Some Tips on Using Online Survey Forms

|

Research ethics protocols vary between and within institutions, but for an online survey it is advisable to include a preamble along these lines:

-

For my [degree title] dissertation at [University name] I am investigating [brief description of topic].

This survey is completely anonymous and none of the data you provide will be passed onto other parties.

If you choose to submit the completed form, your help will be greatly appreciated.

Doing so will be taken as confirming your awareness of its purpose, of my protection of your anonymity,

and of your right to withdraw from this study. Thank you!

Note that research ethics guidelines have special conditions where studies include minors. In the case of online survey forms you may be advised to exclude those under 18. Check with your institution.

Some notes on numeric data. If you are investigating mass media texts it often helps to provide well-sourced demographic data at the outset (see Table 1).

|

Table 1: British newspaper readership demographics

Source: Derived from NRS data, June 2011 |

If you are going to compare the responses of different groups a basic statistical test that is suitable for such comparisons is the Chi-Square Test. Here are some examples of how Chi-Square results are reported:

- Chandler, Daniel & Merris Griffiths (2000) 'Gender-Differentiated Production Features in Toy Commercials' Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 44(3): 503-520; [WWW document] URL http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/short/toyads.html

- Chandler, Daniel & Merris Griffiths (2004) 'Who is the fairest of them all? Gendered readings of Big Brother 2 (UK)'. In Ernest Mathijs & Janet Jones (Eds.) (2004) Big Brother International: Format, Critics and Publics. London: Wallflower Press; [WWW document] URL http://users.aber.ac.uk/dgc/Documents/short/who_is_the_fairest_of_them_all.doc

Remember that when you compare groups you need to ask yourself whether the differences between groups are greater than the differences within them. Extensive tabular data is usually best confined to appendices: select only the most important tabular data for inclusion in the main body of your text. Where you refer to total numbers it is often useful to include percentages (but only where the numbers involved are greater than twenty or so). Avoid any reference to 'significant' findings unless you can specify their statistical significance. Consider where it would be most useful to employ graphical displays such as bar-charts or pie-charts rather than tables. Label tables as 'Table 1' [or whatever] and all other forms as 'Figure 1' [etc.]. Remember to list these at the beginning of the dissertation. While every table or figure requires comment in the main body of the text do not simply repeat the data: help the reader to notice and make sense of patterns in the data.

Some notes on textual analysis. If your data is some kind of text (including audio-visual texts), be clear about your methodology for textual analysis and follow a specific published model. The main options are semiotic analysis, content analysis and discourse analysis. Beware of assuming that the meaning lies within the text rather than in its interpretation. You can avoid privileging yourself as an 'elite interpreter' by seeking the responses of other viewers/readers/listeners.

Some notes on interview data. Bear in mind that transcribing interview data takes a great deal of time - as a rough guide allow at least 2 hours for 10 minutes of audio-recording. Some of my own online notes on interpreting interview data may be useful as a general framework (they were developed for the interpretation of children's talk about television but they have a broader relevance). Do not assume that 'people say what they mean' or 'mean what they say'. Supplement your comments on their words with reference to non-verbal cues. Adopt an established method for your transcription of extracts from such interviews, citing the source for your transcription conventions. For my own students I usually refer them to the transcription conventions employed by David Buckingham as being adequate for most of our purposes (see the table below). Set out the interview somewhat like a playscript, with each speaker's pseudonym in a column to the left. Always anonymise your informants (and assure them in advance that you will do so). It should not be possible to determine who they are from the data you provide. However, you should provide whatever details of their background (age, sex etc.) which seem relevant to interpreting their comments. Data from several interviewees is usually best analysed on a thematic basis rather than interviewee by interviewee. Clearly you will need to focus on themes which relate to your research question(s).

Basic transcription conventions

| (...) | Words undeciphered |

| . | |

| . | |

| . | Talk omitted when irrelevant to the issue being discussed |

| = | Contributions follow on without a break |

| / | Pause of less than two seconds |

| // | Pause of more than two seconds |

| CAPITALS | Emphatic speech |

| [....] | Interjections by an unidentified speaker |

| (?...) | Approximate wording |

| [....] | Stage directions e.g. [laughter] |

| [ | |

| [ | Simultaneous or interrupted speech |

| (&) | Continuing speech, separated in the transcript by an interrupting speaker |

The ways in which you report your 'findings' depend heavily on the methodologies employed so it is difficult to provide general guidelines here. However, it is important to ensure that you go beyond basic description of your data (e.g. simply reporting which television programmes were watched by which groups of people). There must be a substantial element of formal analysis and this analysis should be seen to emerge from your engagement with the data you present; examples should not simply be presented in order to illustrate the points that you wish to make. Whatever kind of data you are dealing with, try to be reflexive in dealing with it: reflect on the constructedness of your data and on your role in constructing it.

In this section you need to summarise your key findings and discuss

possible connections between them. Refer back to your research question(s).

You should relate your own findings to those in any related published

studies outlined in your literature review. Where your findings differ

you should offer a suggested explanation. What light do they shed on

the phenomenon under discussion? What new research questions

are raised by your study?

Make clear what the limitations of your own study are. What

are the limitations of your 'sample'? To what extent are your findings

specific to a particular socio-cultural context? In what ways is your

interpretation of your findings related to your own theoretical

assumptions (outlined earlier)? What insights into the phenomenon

does your study seem to offer? What could others learn from your study?

Discuss any broader implications in relation to your theoretical

framework. This is important because many people discuss 'implications'

as if these were simply logical consequences and leave implicit the

model within which the findings might have such implications. Your

theoretical model must be explicit.

Undergraduates are sometimes unwisely tempted into using the concluding

section of their disertation in order to make general pronouncements on the

topic, often going well beyond the scope of their study.

Conclusions must follow coherently from the evidence; do not be

tempted into speculation, prediction or moralising. Unless specifically

called for, personal opinions should not feature. If you must end with a

quotation, make sure it is a very short one.

Your work should look as professionally done as possible. Even if relatively few marks may be

formally devoted to presentational issues (this varies between departments and institutions),

the 'halo effect' of reading a well-presented dissertation can dispose markers positively towards

your efforts. Most institutions do allow you to submit your draft to a proof-reader to check for

the adequacy of grammar, punctuation, spelling and so on (but check with your own university for its

policy on this issue). Far too many otherwise able students leave proof-reading and other

presentational issues to the very last minute, in which case they may expect to lose marks. Since

'first impressions count', ensure that (at the very least) the first paragraph of each chapter is

well-written.

It is important to make your text easily 'navigable' for the reader,

providing 'signposts' to help them to find their way about.

If you have been writing primarily to clarify your own thoughts (as

many people do) then as you

get closer to presenting your writing to others you must switch your

focus to the convenience of the reader.

It can help to ask a friend to comment on a late draft because it is

not always easy for the writer to spot the problems which readers may

have. If you know who the reader(s) will be, then try to consider the

ways in which they are likely to react to the text. Can you anticipate

any objections which they might have? If so, then you need to revise your

text to address these.

Your dissertation should ‘tell a story’ in the sense that you should

‘set the scene’ (and grab the reader’s attention) at the start, then

try to lead the reader as smoothly as possible from point to point,

working up to some genuine conclusions at the end. Not many of us can write like

this at the first attempt, but a dissertation can be gradually edited into this form.

Check in particular that there are no sudden jumps from one point to another.

Include a contents page (some universities have specific guidelines

for the way in which this should be done). Use subsections within each

chapter (these can usually be included in the contents page). After the

contents page include a list of figures and a list of tables. It is

customary to include an 'Acknowledgements' page: be sure to record your

thanks to all of those who have helped you. Most

universities, faculties or departments have a preferred order in which

introductory sections should appear: check the conventions. Sometimes

the numbering of the introductory pages is in Roman numerals.

Check

whether you are required to use a 'report style' format (with numbered

sections, sub-sections and paragraphs) or more continuous prose.

Occasional lists of short items can help to break up the text: use plain

‘bullets’ for such lists unless there is a good reason to number them.

Don't

forget to number your pages! It may also help to have 'running heads'

which indicate which chapter each page belongs to.

You should double-space your text and use generous margins.

Choose a font size of 12-13 points, and avoid 'san-serif' fonts

(Arial, Helvetica etc.) since these are hard to read in large blocks of text; 'serif' fonts

(such as Times Roman) are more readable in bulk. Use italics only for occasional emphasis

and for the titles of books, journals, newspapers, television programmes etc. Check that you

have included the author, date of publication and page numbers immediately after

quotations in the main body of the text and full references at the end. And check that you

have included your alphabetical list of references, in the preferred form, at the end.

If you include a long quotation (of four lines or more) you should indent it from the

left-hand margin (in which case you should drop the inverted commas). You should avoid

using too many quotations, however: it may give the impression that you have no

ideas of your own and that you accept too uncritically what others have said on the topic. If

you are discussing, for instance, how people feel about something, direct quotations

may be appropriate in social science. But someone else’s bald assertion is

certainly not to be taken as adequate evidence of the truth of what they are saying: just

because the statement appears in print doesn’t of itself make it any more reliable than

remarks in the pub! You should consider the adequacy of your source as evidence.

Normally, you should use a direct quotation only when the writer has put the point

particularly well, and generally a paraphrase is preferable. However, note that the source

of any original ideas expressed in this way must still be given. The cardinal sin in academia is plagiarism, which we may define as the presentation

as one’s own of ideas or phraseology knowingly derived from other writers.

For students, there are very serious penalties for this: it may be treated as an act of fraud.

One may, of course, make use of the ideas of others, since as one wit has observed, ‘when

you take stuff from one writer, it’s plagiarism; but when you take it from many writers, it’s

research’! However, academic writing does require such ‘borrowed’ ideas to be formally

acknowledged.

Your argument may be considerably strengthened by your inclusion of appropriate diagrams, and in some cases illustrations are essential.

Ask yourself how you could usefully visualise some of the key concepts which you are exploring.

If your topic is a visual one (e.g. film, television, the internet) it is even more important to

consider using carefully selected illustrations (such as screenshots). These should never be

purely decorative: they should be discussed in appropriate detail in the text. Indeed,

doing so is often a very productive way to anchor your argument in concrete details.

Consider where carefully thought-out diagrams or tables might help to make a point clearer.

Note that for any textual analysis, it is often both productive for the writer and helpful to the reader

to place closely related images side by side for comparison. Many students who feel that they have little to

say when looking at one image in isolation quickly realise that there is a lot to say about each

image when they are displayed alongside each other. A particularly powerful semiotic technique is the

commutation test: imagine swapping over particular features of each image (such as fonts, colours, postures)

and consider how this affects the interpretation of the image.

Although full-page images (e,g, scans) may be placed in an Appendix, it is always better to have at least

scaled-down versions in the main body of your dissertation, as close as possible to where you discuss them.

Cost-conscious students may be tempted to reproduce such images in greyscale, but colour images are frequently

more effective, and of course where colour is being discussed, such images are essential.

Note that you should at the very least record sources and include

full details of these in your text. Depending on your topic it may also be useful to take some

photographs with a stills camera. If you are lucky enough to have access to a digital camera

you can of course upload these into your document. The incorporation of images which are already in print

can best be accomplished by using a scanner (once again pasting the image files into your text).

If the text is to be published in any form it is of course essential to obtain

copyright permission for any images which you reproduce.

For guidance on capturing stills from film or television, click here.

Illustrations should be labelled as either Figures or Tables, and each should be numbered.

This enables you to refer to them directly ('see Figure 1'),

avoiding the awkwardness of such formulations as 'see the illustration reproduced below' (partly because

when you are writing such texts the relative position of illustrations is constantly shifting). Each should also have a short and

appropriate descriptive caption. A list of Figures and a list of Tables (including their captions and sources) should appear

in the preliminary pages of your dissertation.

Universities, faculties and departments differ in the referencing

formats required. I recommend the Harvard referencing system.

Avoid footnotes and numbered references.

In-text references to sources should be at the end of sentences in

this form:

(Smith 1990: 25-9), omitting page numbers when the reference is

to on-line sources. Note the avoidance of 'page', 'p.' or 'pp.' here.

The list of references should appear at the end of the paper in

alphabetical order as below.

Note re. reference list:

In the UK, undergraduate dissertations are usually around 10,000 words and doctoral theses usually

around 100,000, with other kinds ranging between these limits. However, you need to check the relevant

word counts for your institution and the strictness with which these are enforced (e.g. plus or minus

15%). Reference lists and appendices are not usually included in the word count.

Your institution may have guidelines regarding overall structure and the word counts for each section.

Broadly, you should normally devote at least half of your dissertation to the analysis and discussion of

your findings, though you need to examine carefully what proportion of marks your institution allows

for different elements in order to determine the relative time and attention you give to each part.

Here is my own suggested breakdown of word counts for typical dissertation lengths:

Check to see what the current regulations are concerning whether and how the text should be

bound. In the absence of formal guidelines, these are common default options:

Note also how many copies are required (normally two).

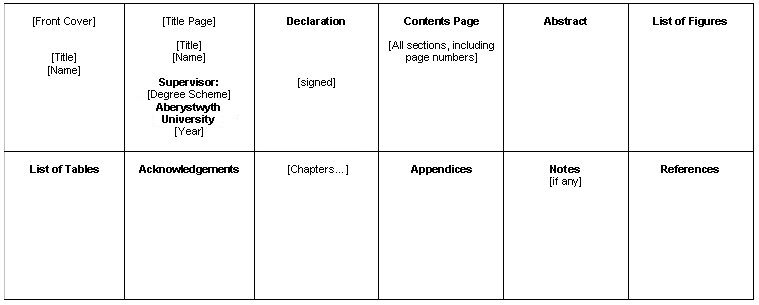

Unless informed otherwise, you should include the following pages in the sequence shown.

The sources of any images must be listed: these can most conveniently be included in the List of Figures.

Blank

consent forms or letters of permission (e.g. to take and include photographs) should appear as an appendix; the

the completed originals should be retained in case of any future query (it is best to submit these in a sealed and

labelled envelope to your supervisor). Other

appendices are likely to be items that would be too intrusive in the main body of the text, such as

blank questionnaires, large tables, full-page scans and so on. Where appropriate (e.g. where the dissertation

involves the study of particular television commercials), a CD including such materials may be included in a pocket

inside the cover.

Universities require a signed declaration (after the Title Page) that what you are presenting as a dissertation is your own work.

The wording varies, so check with your institution. Here is a sample declaration...

I have read and understood the University

statement on plagiarism. This can be found online at:

http://www.aber.ac.uk/academicoffice/plagiarism.rtf

I declare that the attached dissertation is my own, original

work undertaken in partial fulfilment of my degree. I

have made no use of sources, materials or assistance

other than those which have been openly and fully

acknowledged in the text. If any part of another

person's work has been quoted, this either appears

in inverted commas or (if beyond a few lines) is indented.

Any direct quotation or source of ideas has been

identified in the text by author, date and page

number(s) immediately after such an item, and full

details are provided in a reference list at the end

of the text.

I understand that any breach of the fair practice

regulations may result in a mark of zero for this

dissertation and that it could also involve other

repercussions. I understand also that too great a

reliance on the work of others may lead to a low

mark.

[signed]

My own students may

click here for a basic Word template for your dissertation.

If you are, or have been, one of my students and would like me

to write a reference for you, please read

these guidelines

carefully.

Daniel Chandler

Table 1: British women's magazine readerships

Source: Derived from NRS data, June 2011

Figure 1: Front covers of British women's magazines,

May 2012

Table 2: British men's magazine readerships

Source: Derived from NRS data, June 2011

Figure 2: Front covers of British men's magazines,

May 2012

References

Section

Suggested

Percentage10000 words

Undergraduate20000 words

Master's100000 words

Doctoral

Prelims (e.g. Contents Page, Abstract, Acknowledgements)

[not counted]

[not counted]

[not counted]

[not counted]

Chapter 1: Introduction and Rationale [Theoretical Framework]

5%

500

1000

5000

Chapter 2: Literature Review

20%

2000

4000

20000

Chapter 3: Methodology

15%

1500

3000

15000

Chapter 4: Data Gathering and Analysis

[In larger dissertations, this section may constitute several chapters]45%

4500

9000

45000

Chapter 5: Discussion and conclusions

15%

1500

3000

15000

Appendices

[not counted]

[not counted]

[not counted]

[not counted]

References

[not counted]

[not counted]

[not counted]

[not counted]

Declaration

Aberystwyth University