In the early 1960s several influential books and papers were published on the theme of oral versus literate cultures. These included The Savage Mind by the French structuralist anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, a paper on 'The Consequences of Literacy' by the English anthopologist Jack Goody and his colleague the literary historian Ian Watt, The Gutenberg Galaxy by Marshall McLuhan, and Preface to Plato by Eric Havelock. These works and many others since brought to prominence the theme of what came to be called 'orality and literacy' in cultural debates. It is a stimulating but controversial topic with considerable implications for anyone concerned with literacy. It sheds light, for instance, on some of the influences framing the widespread and dominant paranoid myth of the so-called decline of literacy (see Graff 1987).

Someone once wittily remarked that the world is divided into those who divide people into two types, and those who don't. One of those who do asserts that people are either ear people or eye people (Tardif, cited in Synnott 1993, p. 129). This usefully introduces both of our main themes here: dichotomies versus continua, and the ear versus the eye. Indeed, some theorists have argued that an increasing obsession with the visual is what has led us to favour dividing things into tidy categories. For instance, it's only a categorical convention that we have five senses.

Theorists involved in the comparative analysis of modes of communication frequently assume or refer to a binary divide or dichotomy between different kinds of society or human experience: 'primitive' vs. 'civilized', 'simple' vs. 'advanced', 'pre-logical' vs. 'logical', 'pre-rational' vs. 'rational', 'pre-analytic' vs. 'analytic', 'mythopoeic' vs. 'logico-empirical', 'traditional' vs. 'modern', 'concrete' vs. 'scientific', 'oral' vs. 'visual', or 'pre-literate' vs. 'literate'. Such pairings are often also regarded as virtually interchangeable: so that modernity equals advanced equals civilization equals literacy equals rationality and so on. Lucien Levy-Bruhl created a storm of protest early in this century by labelling as 'prelogical' the thinking of people in hunter-gatherer societies. This was hardly surprising, because the apparent implication that some people are intellectually inferior has alarming political potential.

Binary accounts have been referred to as 'Great Divide' theories. Such theories tend to suggest radical, deep and basic differences between modes of thinking in non-literate and literate societies. They are often associated with attempts to develop grand theories of social organization and development. Dualities are prominent in the commentaries of structuralist theorists. Like any form of simplification they can be interpretatively illuminating. However, the sharp division of historical continuity into periods 'before' and 'after' a technological innovation such as writing assumes the determinist notion of the primacy of 'revolutions' in communication technology. And differences tend to be exaggerated. Reviewing the research literature, Ruth Finnegan comments that 'it is difficult to maintain any clear-cut and radical distinction between those cultures which employ the written word and those that do not' (cited in Olson 1994, xv).

One defence of a great divide theory by Jack Goody suggested that to deny any significant distinction between non-literate and literate societies involved adopting the widely criticized stance of cultural relativity (Goody et al. 1968, p. 67). Goody argues that 'general' rather than radical differences still exist between non-literate and literate cultures which are greater than the differences one may find between various literate practices. Another reaction to criticisms of a great divide is offered by David Olson and Angela Hildyard. These commentators, convinced of the key role of literacy in developing intellectual competence, declare that if there is no difference between pre-literate and literate mentality then we could hardly justify compulsory schooling (Olson & Hildyard 1978 cited in Street 1984, p. 19). They would clearly prefer not to acknowledge that a primary function of schooling is social control in the interests of ruling elites (see Graff 1987).

Harvey Graff refers to the 'tyranny of conceptual dichotomies' - such as literate and illiterate, written and oral, print and script - in the study and interpretation of literacy. He declares that 'None of these polar opposites usefully describes actual circumstances; all of them, in fact, preclude contextual understanding' (Graff 1987, p. 24). The interpretive alternatives to Great Divide theories are sometimes called 'Continuity' theories: these stress a 'continuum' rather than a radical discontinuity between oral and literate modes, and an on-going dynamic interaction between various media (Finnegan 1988, pp. 139, 175).

One apologist for a great divide theory insists that continuity theories suggest 'that orality and literacy are essentially equivalent linguistic means for carrying out similar functions. Psychologically their differences are not important... The role of literacy is more social and institutional than it is psychological or linguistic.' On the other hand, great divide theories argue 'that orality and literacy, whilst importantly interactive... allow old functions to be served in new ways and to bring new functions into view. In doing so, they realign psychological processes and social organization' (Olson & Torrance 1991, p. 7).

The crosscultural cognitive psychologists Michael Cole and Sylvia Scribner in their important book on The Psychology of Literacy (1981) have avoided both the stance that thinking in oral and literate modes is basically the same and also 'the Great Cognitive Divide'. They note more moderately from their research amongst the Vai people of Liberia that literacy there appeared have no general cognitive consequences. Their research contradicted the common view that literacy leads inevitably to higher forms of thought. 'On no task - logic, abstraction, memory, communication - did we find all nonliterates performing at lower levels than all literates... We can and so claim that literacy promotes skills among the Vai, but we cannot and do not claim that literacy is a necessary and sufficient condition for any of the skills we assessed' (Cole & Scribner 1981, p. 251). They also found that schooling rather than literacy appeared to be the significant cause of some changes in cognitive skills involved in the logical functions of language. They argued that 'the tendency of schooled populations to generalize across a wide range of problems occurred because schooling provides people with a great deal of practice in treating individual learning problems as instances of general classes of problems'. They emphasized the importance of considering the use of literacy in different social contexts, and concluded only that 'particular practices promote particular skills'. Patricia Greenfield declared that Scribner and Cole's study 'should rid us once and for all of the ethnocentric and arrogant view that a single technology suffices to create in its users a distinct, let alone superior, set of cognitive processes' (cited in Olson 1994, 20).

Some commentaries refer to idealized types of society as if 'orality' and 'literacy' were dichotomies or polar opposites. Dichotomies and polarization are often intended to simplify accounts of cultural diversity. So cultures characterized as representative of 'orality' are small-scale, rural, communal, nonindividualistic, authoritarian and conformist, whilst those characterized as exemplars of 'literacy' are large-scale, urban-industrial, individualistic, heterogeneous and rationalistic. Contrasting societies can be illuminating, especially in making us aware of our own taken-for-granted cultural assumptions. But the distinctions between literate and non-literate societies (or phases in our own society) are not as clear-cut as is often assumed. And some characteristics of non-literate societies cannot simply be attributed to non-literacy.

Those in non-literate societies do not necessarily think in fundamentally different ways from those in literate societies, as is commonly assumed. Differences of behaviour and modes of expression clearly exist, but psychological differences are often exaggerated. Although one commentator, Peter Denny, argues that 'decontextualization' seems to be a distinctive feature of thinking in Western literate societies, he nevertheless insists that all human beings are capable of rationality, logic, generalization, abstraction, theorizing, intentionality, causal thinking, classification, explanation and originality (in Olson & Torrance 1991, p. 81). All of these qualities can be found in oral as well as literate cultures.

It is important to be aware of the similarities as well as the differences between non-literate cultures and our own. Nor should we exaggerate the similarities between various non-literate societies, or indeed between literate societies, as such labels encourage us to do. The differences between non-literate societies can be as striking as any between literate and non-literate societies. And there can be a great variety of modes of 'orality' and 'literacy' within a single society. Even the practices of individuals in their use of these modes may exhibit considerable variety from situation to situation.

There is a real danger that seeing non-literates societies as different from ours may be associated with seeing those who live in such societies as inferior to ourselves. The notion of 'primitive mentality' is now rejected by most anthropologists, though it survives amongst some conservative theorists. And the alternative danger of romanticizing 'oral' societies as more 'natural' than those in which we live is no less a problem.

There are several books which offer excellent correctives to the wild generalizations of some less critical writers on literacy and orality. I recommend in particular Ruth Finnegan's Literacy and orality, Brian Street's Literacy in Theory and Practice, Michael Cole and Sylvia Scribner's The Psychology of Literacy and Harvey Graff's The Labyrinths of Literacy. Whilst emphasizing the primary importance of close studies of actual uses of orality and literacy, Finnegan concludes that 'looking for recurrent patterns and differences can still be illuminating in the study of human societies even if one has to treat them with caution, and (as I would urge) avoid the idea of universally applicable causal mechanisms based on specific technologies' (Finnegan 1988, p. 168).

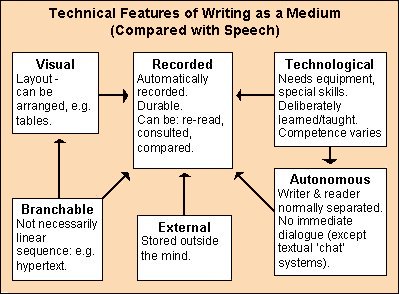

Spoken word Written word

aural visual

impermanence permanence

fluid fixed

rhythmic ordered

subjective objective

inaccurate quantifying

resonant abstract

time space

present timeless

participatory detached

communal individual

Some dichotomies of the ear and eye

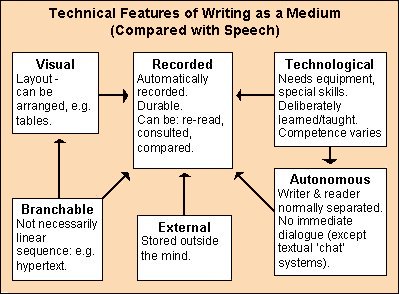

Clearly, there are fundamental technical differences between the medium of writing and the medium of speech which constitute 'constraints' on the ways in which they may be used, but I do not wish to adopt the stance of hard technological determinism according to which such features would determine the ways in which they are used.

Whatever the technical constraints of the medium, it is useful to remind ourselves of the social context of its use. We need to consider the overall 'ecology' of processes of mediation in which our behaviour is not technologically determined but in which we both use a medium and can be subtly influenced by our use of it.