- slapstick comedy;

- romantic comedy, including 'screwball comedy' and musical comedy;

- musical biography; and

- fairy tale.

- adventure films, including 'the swashbuckler' and 'survival films' (the war movie, the safari film, and disaster movies);

- the western;

- 'fantastic genres', including fantasy, horror and science fiction; and

- 'antisocial genres', including the crime film (the gangster film, the G-man film, the private eye or detective film, the film noir, the caper film) and so-called 'weepies' (or 'women's films').

- Contents page

- The problem of definition

- Working within genres

- Constructing the audience

- Advantages of generic analysis

- D.I.Y. Generic analysis

- Appendix 1: Taxonomies of genres

- Appendix 2: Generic textual features of film and television

- References and suggested reading

- Genre Theory Links

An Introduction to Genre Theory

Daniel Chandler

Appendix 1: Taxonomies of genres

The limitations of genre taxonomies have been alluded to. However, this is not to suggest that they are worthless. I have noted already that the broadest division in literature is between poetry, prose and drama. I will not dwell here on literary genres and sub-genres. Despite acknowledging the limitations of taxonomies, Fowler (1982) offers the most useful and scholarly taxonomy of literary genres of which I am aware. Mass media genres do not correspond to established literary genres (Feuer 1992, 140). After a brief consideration of the most fundamental genre frameworks I will offer here a single illustrative taxonomy of fictional films.

Traditional rhetoric distinguishes between four kinds of discourse: exposition, argument, description and narration (Brooks & Warren 1972, 44). These four forms, which relate to primary purposes, are often referred to as different genres (Fairclough 1995, 88). However, it may be misleading to treat them as genres partly because texts may involve any combination of these forms. It may be more useful to classify them as 'modes'. In particular, narrative is such a fundamental and ubiquitous form that it may be especially problematic to treat it as a genre. Tony Thwaites and his colleagues dismiss narrative as a genre:

-

Because narratives are used in many different kinds of texts and

social contexts, they cannot properly be labelled a genre.

Narration is just as much a feature of non-fictional genres...

as it is of fictional genres... It is also used in different kinds

of media... We can think of it as a textual mode rather than a

genre. (Thwaites et al. 1994, 112)

In relation to television, and following John Corner, Nicholas Abercrombie suggests that 'the most important genre distinction is... between fictional and non-fictional programming' (Abercrombie 1996, 42). This distinction is fundamental across the mass media (for its importance to children see Buckingham 1993, 149-50 and Chandler 1997). It relates to the purpose of the genre (e.g. information or entertainment). John Corner notes that 'the characteristic properties of text-viewer relations in most non-fiction television are primarily to do with kinds of knowledge... even if the programme is designed as entertainment. The characteristic properties of text-viewer relations in fictional television are primarily to do with imaginative pleasure' (Corner 1991, 276).

Despite the importance of the distinction between fictional and non-fictional genres, it is important also to note the existence of various hybrid forms (such as docudrama, 'faction' and so on). Even within genres acknowledged as factual (such as news reports and documentaries) 'stories' are told - the purposes of factual genres in the mass media include entertaining as well as informing.

In relation to film, Thomas and Vivian Sobchack offer a useful taxonomy of film genres (Sobchack & Sobchack 1980, 203-40). They make a basic distinction, on a level below that of fiction and non-fiction, between comedy and melodrama (adding that tragedy tends to appear in 'non-formula' films).

The Sobchacks list the main genres of comedy as:

They list the main genres of melodrama as:

Whilst the Sobchacks offer an extremely useful outline of the textual features of films within these genres, part of the value of such taxonomies may be the way in which they tend to provoke immediate disagreement from readers!

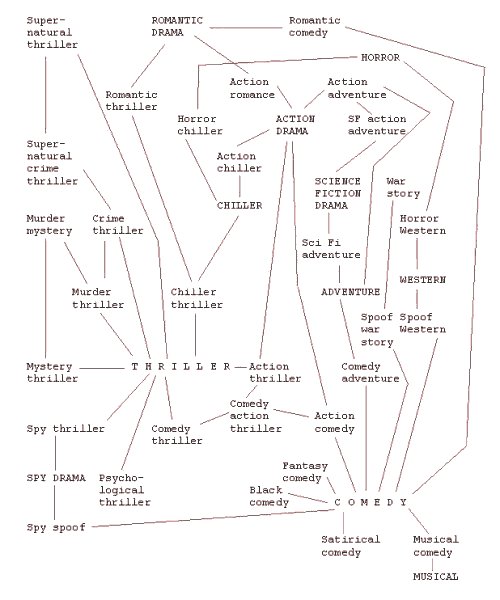

The generic labels employed by film reviewers in the television listings magazines are worthy of investigation. Here is a personal attempt to map, purely by association, the labels used in the British television listings magazine What's On TV over several months in 1993.

Contents